MARKER BIOGRAPHIES

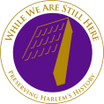

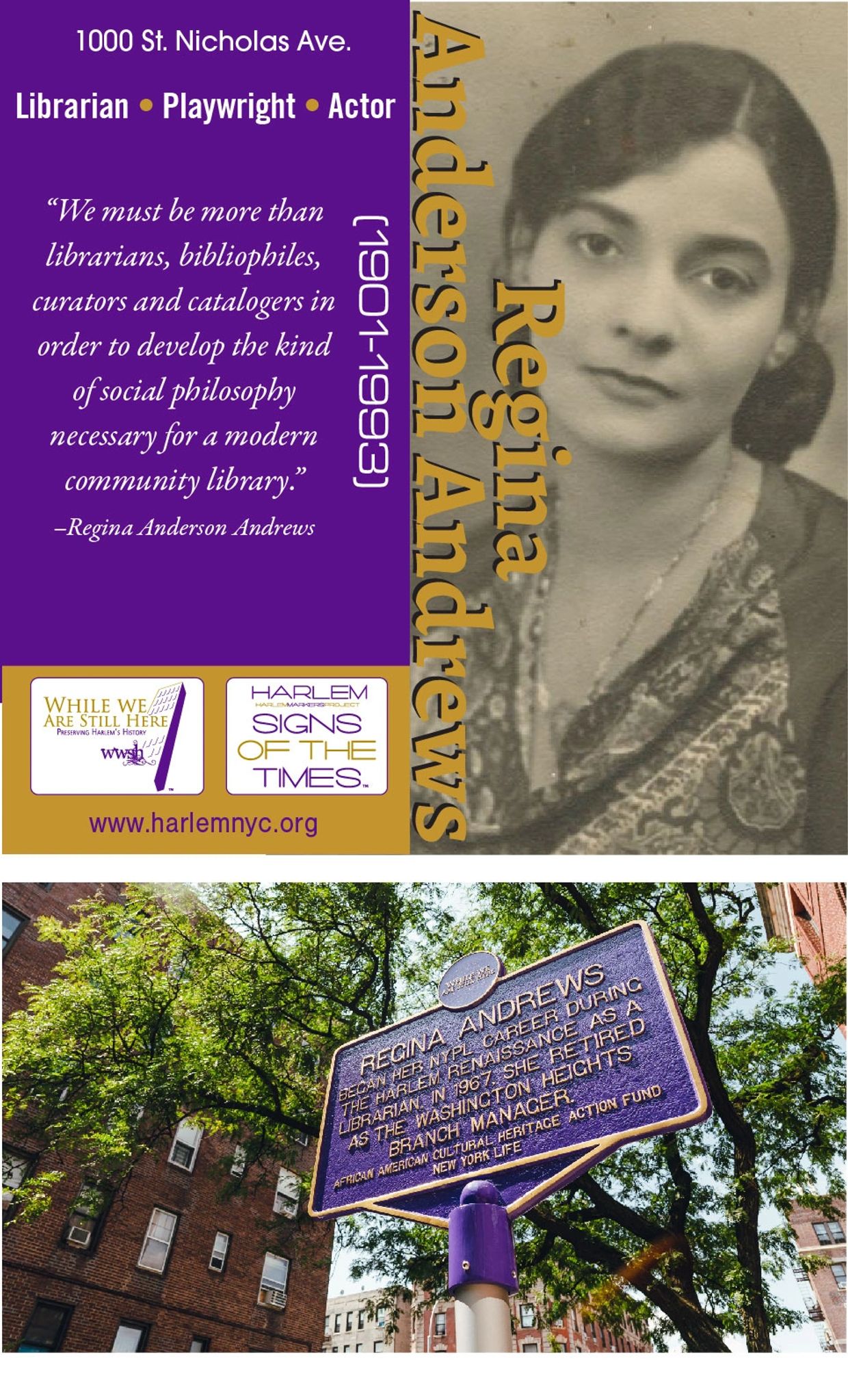

1901-1993 | 1000 ST. NICHOLAS AVE.

“It can be truly said that the community theater is an important factor in the educational, social, and recreational life of the people. It supplies an outlet for self-expression which is inherent in all of us. It provides a stimulant or an incentive to personality improvement. In many cases the little theater has been the instrument for unearthing real talent. Perhaps one of the most productive agencies in this regard has been our own little theater group, The Harlem Experimental Theatre. The story of the struggles and achievements of this group is representative of similar groups in other communities. The need it has filled in a Negro community like Harlem cannot be estimated.”

—Regina Anderson Andrews

The powerful and lasting impact that Regina Anderson Andrews herself would have on the Harlem community could not have been estimated, either. The petite, soft-spoken librarian arrived in Harlem in 1922 when she was just twenty-one years old, full of innovative ideas and a passion to put them into action. She saw the library as a focal point in the community, providing more than books, but could also be a also be a center for learning, theater, intellectual exchange, the arts, and academic tutoring. From her perspective, the library could also aid those in need of social services, and was a place to create and build a mecca for human rights. Not only did Regina Anderson Andrews become the first African American woman to head a New York City Public Library branch, she also became a respected playwright, international diplomat, and community activist.

Andrews was born in Chicago, Illinois in 1901. Her mother, Margaret Anderson, was a notable ceramics artist. Her father, William Grant Anderson, was a skilled attorney nicknamed "Habeas Corpus" because he got so many people out of jail at a time when Black citizens were denied a fair trial and often held without even being charged with a crime. Andrews was very close with her father and well aware of his mostly successful battles with the court systems and his legal actions against lynching. She would later write and produce the play, Climbing Jacob’s Ladder (1931), about a lynching that happened while people prayed in church. After college, Andrews’s high score on a civil service examination landed her a job as a Chicago librarian before she moved to New York City.

Anderson applied for a library position and was delighted when she was soon called in to the main library on 42nd Street and Fifth Avenue for an interview. The library administrator questioned her answers on the job application. He wanted to know why she had put “American” as her race. She replied, “I am an American, what else would I be?” The interviewer informed her, “You’re not an American. You’re not white.” He told her that because she was Colored, she would be sent to work in Harlem. At the time, Andrews knew very little about the neighborhood because she lived in the 42nd Street YWCA. He suggested she find roommates and move to Harlem, which she did and in a big way.

A three-bedroom apartment in a swanky building at 580 St. Nicholas Avenue became home for Anderson and her two roommates. They named their place on Sugar Hill “Dream Haven,” and were some of the first tenants to integrate the posh address. The famous performer, Ethel Waters, was their neighbor. At the time, many affluent, prominent African Americans were moving to Sugar Hill, and through her job at the 135th Street branch, Anderson met many future luminaries, who spearheaded the Harlem Renaissance. Soon, the three young women had turned their apartment into a literary salon, where African American artists and intellectuals socialized and exchanged ideas. Refreshments were served on beautiful dinnerware produced by Anderson’s mother. Guests often included W.E.B. Du Bois, Countee Cullen, Arna Bontemps, Langston Hughes, Eric Walrond, A’Lelia Walker, Jessie Fauset, Alain Locke, Charles S. Johnson, and many others. Zora Neale Hurston even slept on the sofa when she first arrived in Harlem.

Although Anderson and her flat mates were zealous about their salon and events, the three were on a limited budget and barely able to pay the rent. Their mentor, Du Bois, would treat them to outings and meals at the end of the month when the women ran low on money. They would often call him to ask him if he was in town and he would jokingly reply, “I presume you’re hungry.”

On March 21, 1924, Anderson attended the dinner she had helped Jessie Fauset organize to celebrate Fauset’s new book, There is Confusion. The list of 110 invitees included Du Bois, James Weldon Johnson, Jean Toomer, Langston Hughes, Hubert Thomas Delany, and Claude McKay. Several credit the gathering as the beginning of the Harlem Renaissance, though during the era, it was called the New Negro Renaissance. Alain Locke, master of ceremonies for the dinner and a Howard University professor, compiled and edited a special issue, “Harlem: Mecca of the New Negro,” for the progressive magazine, Survey Graphic. Suddenly, the Harlem-based writers were in the news and the Renaissance was officially launched.

At her library job, Anderson was creating a safe and creative space for African American writers at the 135th Street branch. She reserved desks and quiet time for the artists to hone their craft. She and Du Bois cofounded the Krigwa Players, a company of Black actors performing plays by Black authors that performed at her library. Later, the Krigwa Players became the Negro Experimental Theatre (NET) (also known as the Harlem Experimental Theatre) and in 1931, produced Anderson’s one-act play Climbing Jacob’s Ladder. The Negro Experimental Theatre inspired little theatre groups across the country, and it was especially influential in the encouragement of serious Black theatre and Black playwrights. Anderson spoke about the NET on the radio: “Plays and revues of black people were on downtown stages, but few were presented in Harlem where the black playwright’s audience lived. We had few plays to work with and almost none of recent date…. We have given special attention to the production of original unpublished plays by Negroes. After four years of work with our theater, I feel that our greatest contribution to the cultural achievement of the community will be in this production of original plays…. We must develop our Negro drama to include the problem of the Negro worker and the present-day Negro social drama theme.”

Anderson knew firsthand about the problem of the Negro worker as she faced discrimination at her workplace. Although she was promoted because she was an outstanding employee, her pay did not reflect those promotions. Du Bois came to her defense and after a battle of blazing hot communications among all involved, Anderson was finally paid a fair wage. In 1938, she become the first Black supervising branch librarian with the NYPL and, eventually, headed the Washington Heights branch. She continued offering excellent programming to her patrons and started the event, “Family Night at the Library, which served immigrants and refugees from around the world as well as Puerto Ricans and African Americans. Featured speakers like Margaret Sanger traveled uptown at Anderson’s invitation, and she was proud that her library had the largest collection of Spanish books in the system. At the 1939 World’s Fair in New York City, Regina Anderson was one of ten African Americans to be honored for her contributions.

On the home front, Andrews’s husband, Attorney William T. Andrews, served as an NAACP lawyer and became the first Black New York State assemblyman. Like her apartment as a single woman, their home was also a welcoming place for the movers and shakers in the community. She was active with the NAACP and Urban League as well as organizations that supported women’s rights like the National Council of Women of the United States. She represented the National Urban League as a member of the United States National Commission for UNESCO and traveled to Europe, Africa, and Asia from 1958 to 1965. Over the years, “Family Night at the Library” was still going strong and Anderson often invited diplomats and cultural bearers she met through her UNESCO work to speak.

Regina Anderson Andrews retired from the New York Public Library in 1966 after a storied forty-four years with the institution. In 1968, Anderson was a consultant for the Metropolitan Museum of Art's exhibit, “Harlem on My Mind.” Later, Anderson contributed to The Black New Yorkers partially due to her negative experience working on the Met’s exhibit, and she eventually resigned from the research advisory council. She coedited the Chronology of African-Americans in New York, 1621–1966 (1971) with former roommate, Ethel Ray Nance.

In 1987, Anderson donated her extensive collection of papers, photographs, and books from both her and her family, to the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. On May 23, 1993, a few days after what would have been her 92nd birthday, Regina Anderson Andrews’s memorial service was held at the Schomburg Library on 135th Street, the very same place where she started her legendary library career.

More Biographies: J. Rosamond Johnson | Larry Neal | Marcus Garvey | Coleman Hawkins

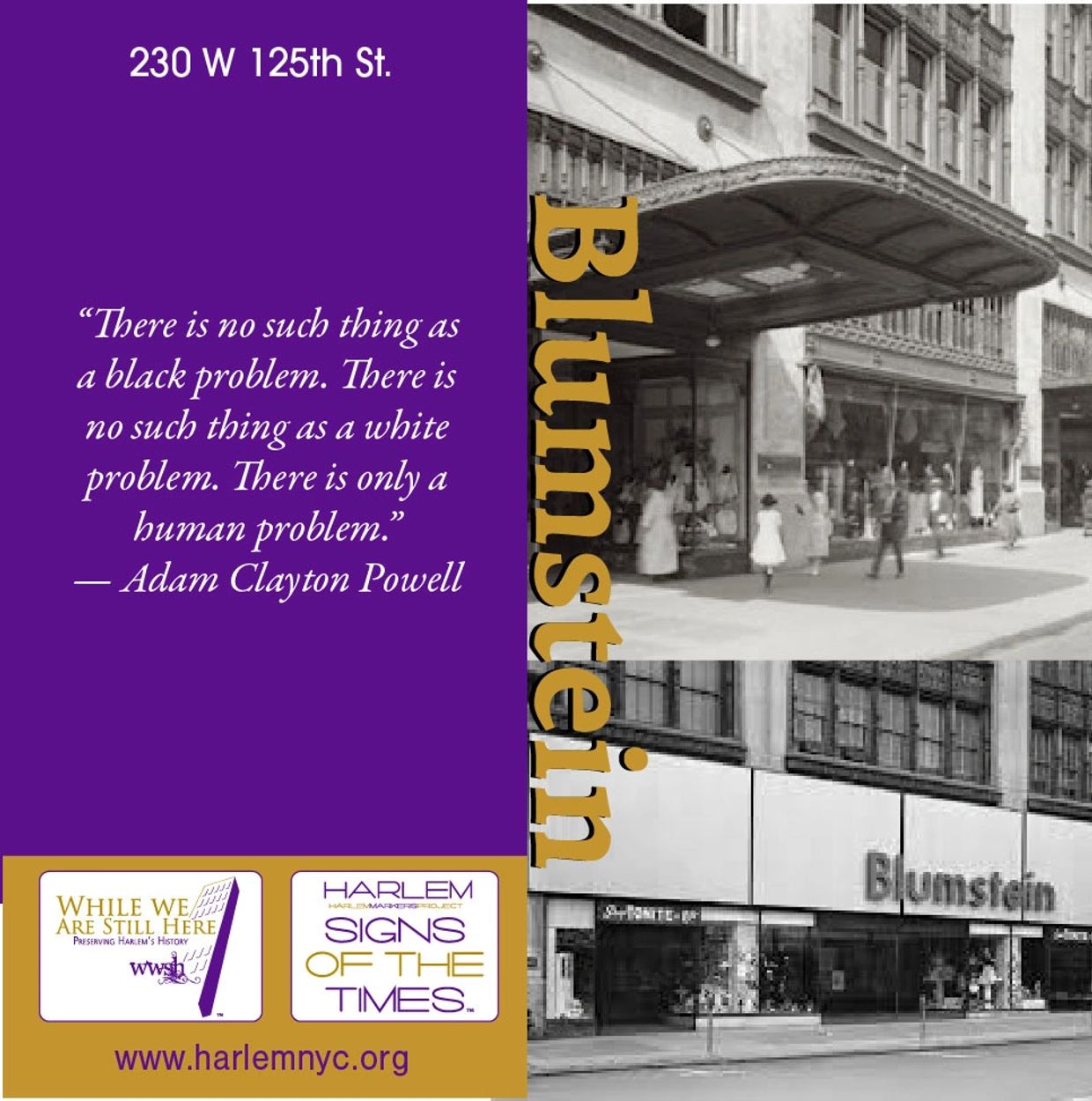

Blumstein

230 W. 125th St.

More information coming soon

Copyright © 2025 While We re Still Here - All Rights Reserved.

Powered by EM Designs Group

Cookie Policy

This website uses cookies. By continuing to use this site, you accept our use of cookies.