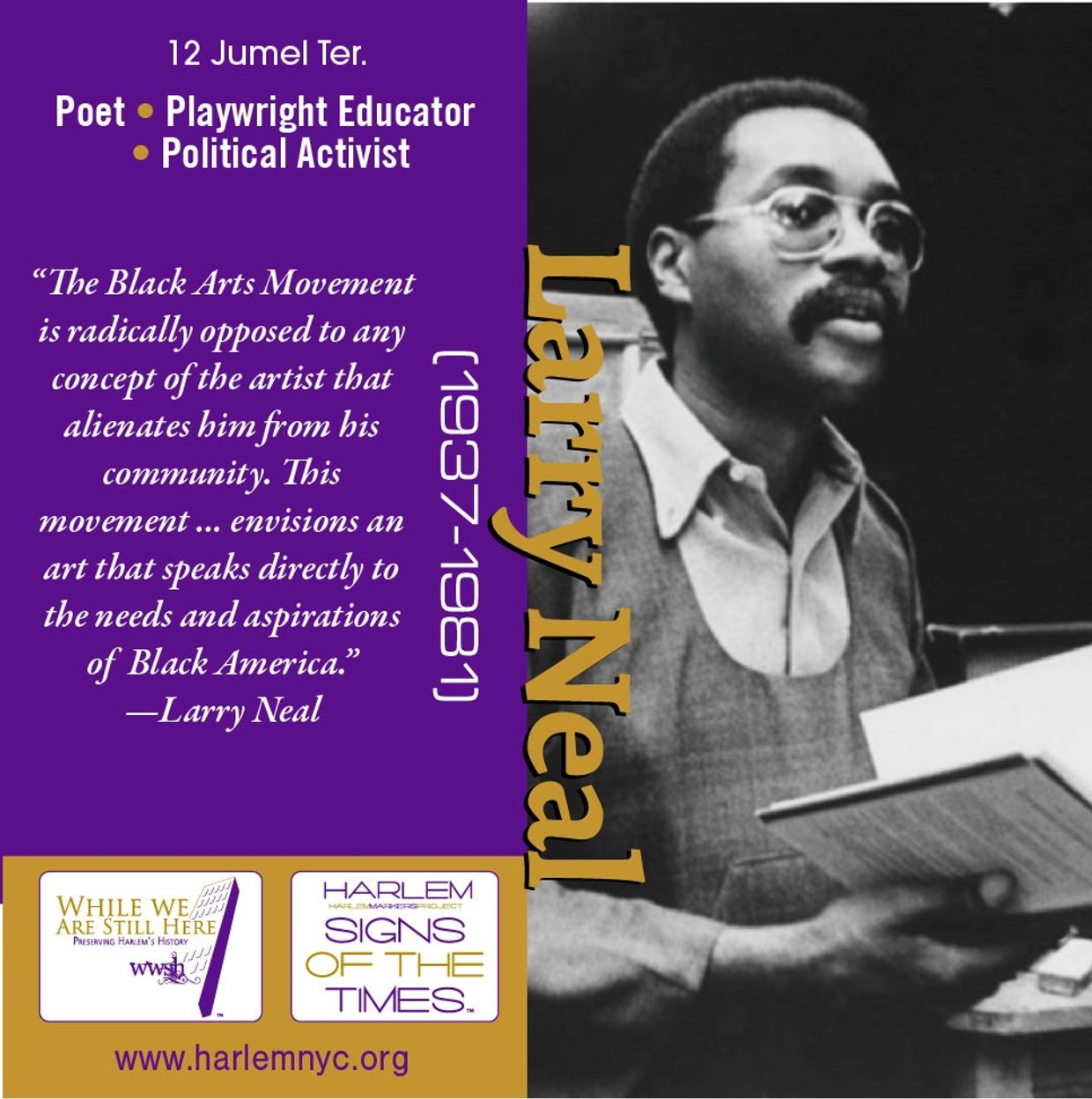

MARKER BIOGRAPHIES

Lawrence “Larry” Neal

1937-1981 | 12 Jumel Ter.

“It is a profound ethical sense that makes the Black artist question a society in which art is one thing and the actions of men another. The Black Arts Movement believes that your ethics and your aesthetics are one.

—Larry Neal

Lawrence P. Neal was a scholar, professor, poet, critic, and playwright. A visionary, he was one of the engineers of the Black Arts Movement, which emerged in the 1960s. He worked closely with Amiri Baraka, founder of the Black Arts Repertory Theater in Harlem, to reestablish an arts practice that not only reflected the issues, challenges, and victories within the Black community, but also married politics and aesthetics in a responsible and restorative way. The goal was to create poetry, novels, visual arts, and theater to reflect pride in Black history and culture and to affirm that art was a means to awaken Black consciousness and achieve liberation.

Throughout history and in many different cultures, art has been at the forefront of revolutionary thought and influence. Although enslaved Africans were ripped from their own cultures, the traditions of art being of the people and for the people remained strong. As colonization and oppression destroyed centuries-old concepts of cultural belonging, language, religion, artforms, and heritage, the purpose of art as a means of liberation endured. Enslaved people created stunning hairstyles, whose braid designs were also maps of escape routes. They shared plans for gaining freedom by hiding them within song lyrics. Both these beautiful art forms and others propelled generations to fight back. Larry Neal translated those ancient values of using art to communicate, rebel, and heal into contemporary understanding and practice. He proclaimed that ''Most writers are not thinking about making it on Broadway. The young black writers are re-evaluating Western esthetics and the traditional role of the writer and the social function of art.”

Mr. Neal published an essay in 1969, which clarified the goals of the Black Arts Movement. Titled “Any Day Now: Black Art and Black Liberation,” Neal sought “to link, in a highly conscious manner, art and politics in order to assist in the liberation of black people.” He and Amiri Baraka collaborated on Black Fire: An Anthology of Afro-American Writing, which critics deemed, ''a literary landmark.''

From 1963 to 1965, Mr. Neal served as the arts editor of the Liberator, a Black nationalist magazine. It was the first publication to feature his work regularly and he later wrote for the Partisan Review, the Tulane Drama Review, Ebony, Black Scholar, Freedomways, Black World, First World, and The New York Times. Among his writings are two books of poetry, Black Boogaloo and Hoodoo Hollerin' Bebop Ghosts.

Mr. Neal was also a respected music critic and wrote for Cricket, a publication devoted to African American music, which espoused a Black nationalistic philosophy. He was close with several jazz musicians, many of whom had been classically trained in European music traditions, but took up the challenge to use the art form to create songs that expressed a prideful, progressive way of thinking.

In 1979, Mr. Neal’s play The Glorious Monster in the Bell of the Horn was produced at the New Federal Theater by famed director, Woodie King. Jazz luminary, Max Roach, wrote the score and the play was met with critical acclaim from both the Black community and the mainstream. Mr. Neal’s work and influence always demonstrated his belief that "Black Art is the aesthetic and spiritual sister of the Black Power concept."

He was an esteemed professor of literary subjects, and taught at Drexel and Yale universities and Lincoln, Wellesley, and Williams colleges. In 1971, he was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship and held a chair in Humanities at Howard University. Serving as executive director for the District of Columbia Commission on the Arts and Humanities from 1976 to 1978, Mr. Neal had a major impact on the Commission although many doubted that a poet could be a competent bureaucrat. He said, "There is precedent for combining art and work in government, "Malraux did it. So did Neruda. Government is people. What is life without art and ideas? Government can help take art to people. Look at what happened in the '30s with the WPA."

Larry Neal and others who spurred the Black Arts Movement altered forever the way African American art is presented. Indeed, Indigenous Americans, Latin Americans, Asian Americans, and others not represented in the arts, began to take notice. When Mr. Neal challenged the arts “business,” maybe two or three Black writers were included in university curricula. Of the books published in the twentieth century, 95 percent were penned by white authors. Books written about Black people had a better chance of publication if they were written by white authors. The Black Arts Movement encouraged a smattering of Black-owned publishing houses, Black editors, and Black literary agents.

Mr. Neal helped to shape the manuscripts of many Black writers through actual editing and by discussing the fine points of the Black Arts ethos. Today, the number of Black published writers is still very low, but the Black Arts Movement “woke up” readers of color, who demanded their “own” works be written by authors from their own communities.

Mr. Neal died at a very young age. He was forty-two years old and “walked on” while at Colgate University facilitating a theater workshop. He had just completed a jazz series for WGBH-TV of Boston and a film script on musical improvisation for Clark College in Atlanta. He was assisting percussionist Max Roach write his autobiography and working on a three-volume series on the writings of Zora Neale Hurston, about whom he had also written a screenplay.

Mr. Neal is remembered as championing the importance of cultural work to the Black freedom struggle. He said, “So when we speak of an esthetic, we mean more than the process of making art, of telling stories, of writing poems, of performing plays. We also mean the destruction of the white thing. We mean the destruction of white ways of looking at the world.” Lawrence P. Neal took on an ambitious task of “expressing the soul of the black nation” and ushering in the “cultural and spiritual liberation of Black America.”

More Biographies: J. Rosamond Johnson | Marcus Garvey | Malcolm X | Coleman Hawkins | Regina Anderson Andrews

Copyright © 2025 While We re Still Here - All Rights Reserved.

Powered by EM Designs Group

Cookie Policy

This website uses cookies. By continuing to use this site, you accept our use of cookies.