MARKER BIOGRAPHIES

Pauli Murray

225 W. 110th St.

More information coming soon

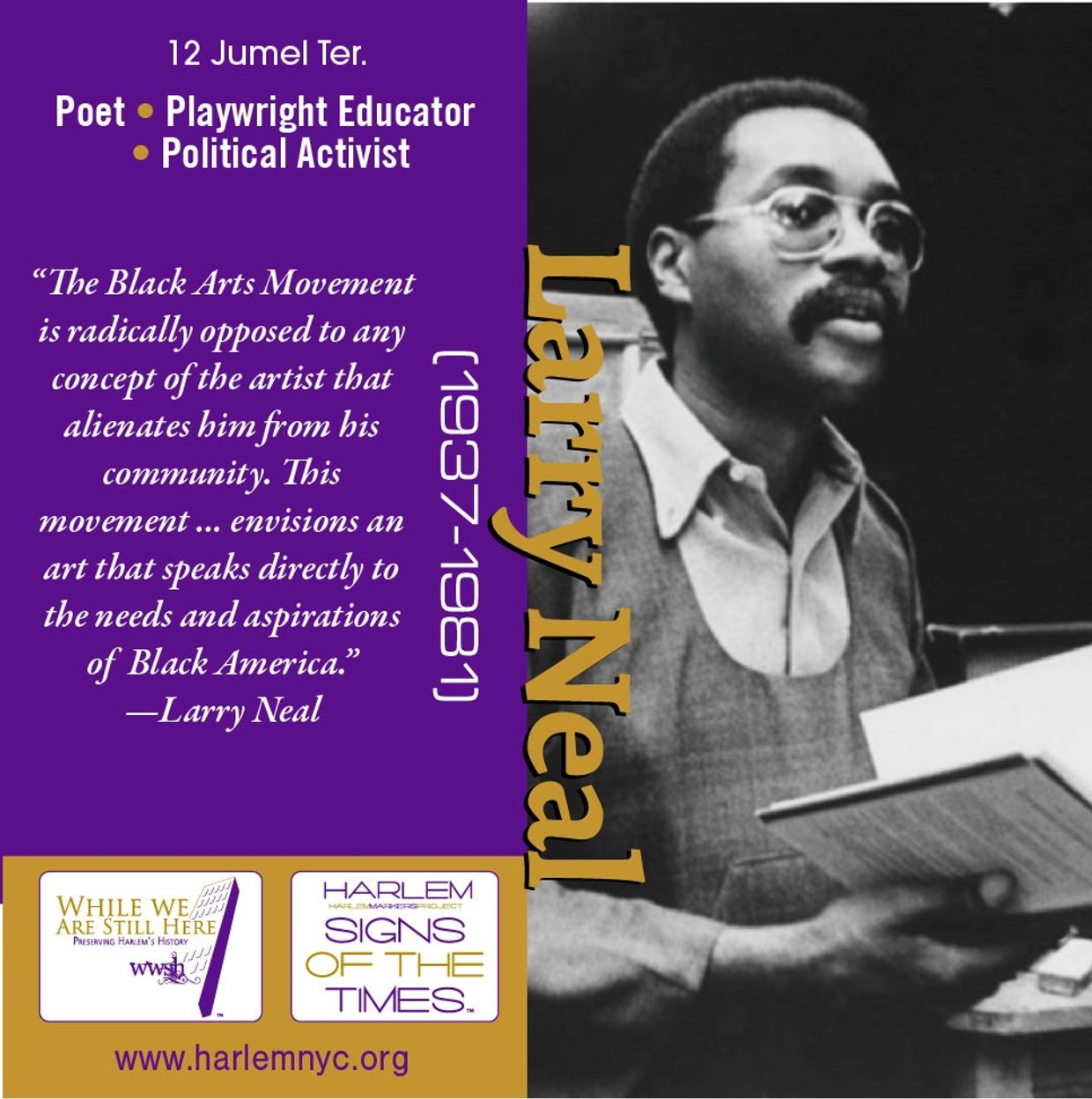

Larry Neal

12 JUMEL TER.

More information coming soon

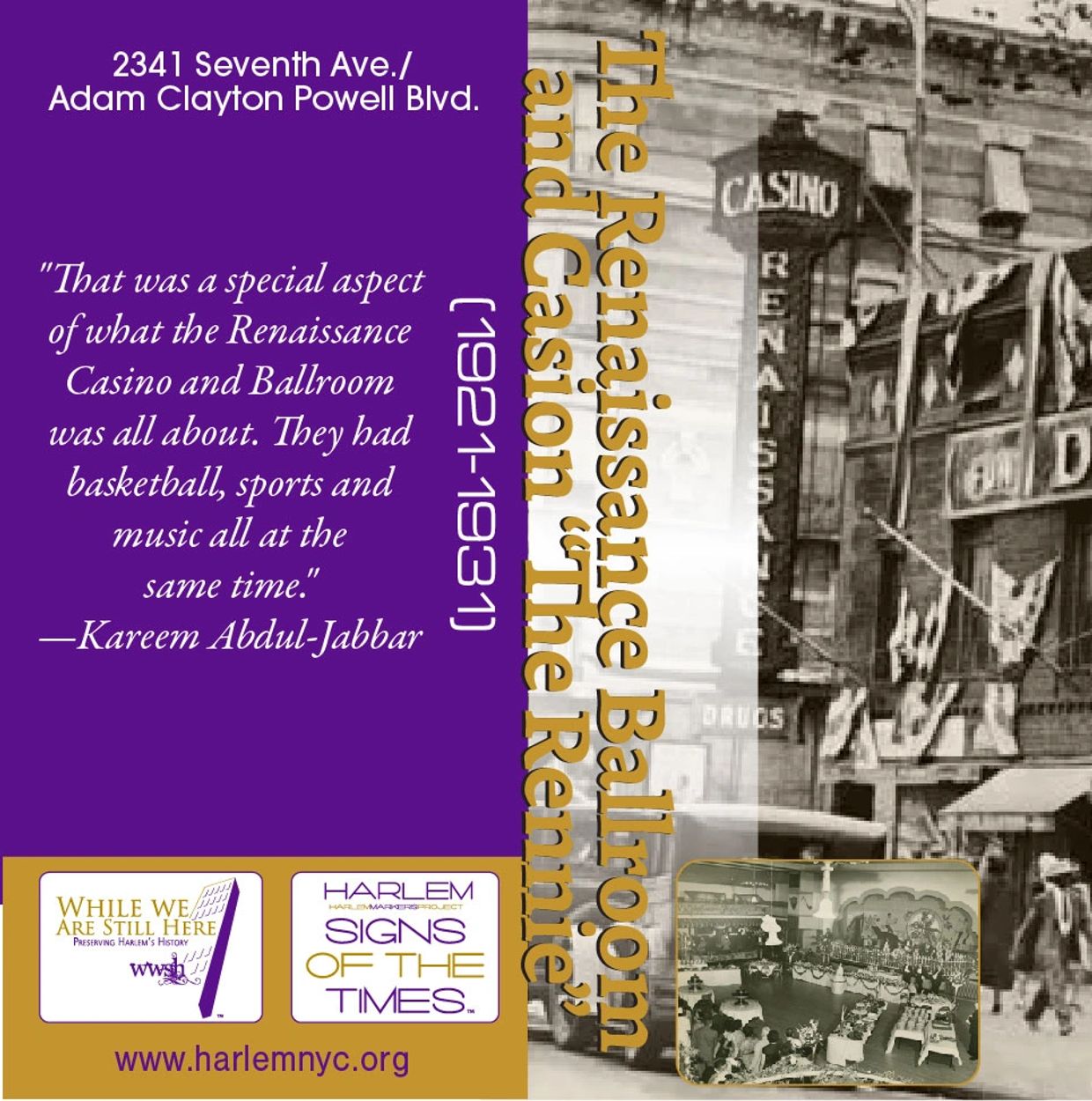

“THE RENNIE”

2341 Seventh Ave./Adam Clayton Powell Blvd.

“This theatre should appeal to your sense of racial pride.” Advertisement for the grand opening of The Renaissance Theater and Casino

January, 1921 was an icy month in Harlem with the temperature rarely reaching even fourteen degrees. The freezing, winter wind ruffled the fancy coats and dresses of the crowd lined up on West 137th Street and Seventh Avenue, threatening to blow off hats and scarves. But no matter how bitter the cold, the people were warmed by the anticipation of entering the Harlem Renaissance Theater and Casino on its opening night. The eager patrons were lured by the syncopated rhythm of a ragtime band floating out from behind the massive doors. The excitement was palatable outside the vast, new, multi-use complex, a stunning shrine to the brilliance and determination of the Caribbean entrepreneurs who created this entertainment venue for Harlemites. The building’s architecture celebrated the magnificence of North Africa with its Moroccan- and Moorish-inspired designs. Indeed, neighborhood music and art lovers now had a center worthy of African American innovations, talents, which also welcomed Black patrons, unlike the Cotton Club and others. At the time, white New Yorkers traveled uptown to enjoy Harlem nightclubs, but although the entertainers were Black, the segregated venues only catered to white clientele.

The concept of constructing a building that could accommodate varied events was ingenious and way ahead of its time. Harlem transplants William H. Roach from Antigua, and Cleophus Charity and Joseph H. Sweeney from Montserrat were the founding builders of the Renaissance Complex and were members of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). Their firm, the Sarco Realty & Holding Company, Inc., included the public in their fundraising efforts for the project by selling shares for ten cents. They were determined to provide a gathering place for musicians, dancers, and thespians, and for holding events, such as cotillions and basketball games. Sarco Realty owned and managed the building until 1931.

The Renaissance Theater & Casino boasted a 900-seat theater, casino, and ballroom, and was a mecca for Black musicians and their fans. Black music luminaries that performed there included Louis Armstrong, Fletcher Henderson, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Cab Calloway, Lionel Hampton, Cootie Williams, Bessie Smith, Lena Horne, Vernon Andrade, Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald. African American theater performances graced the stage at the Rennie and Harlem had its own Broadway, rivaling any productions downtown. Oscar Michaux, known as the first Black filmmaker enthralled Rennie audiences with his silent and sound films. He produced more than forty-four films and was also an author.

Dance marathons, weddings, and competitions were popular at the Rennie, along with college formals and proms. As the venue became more and more popular, its nickname lovingly became the “Renny” or “Rennie.” Former New York City mayor, David Dinkins, and his wife held their wedding reception at the famed establishment. The beloved poet, Langston Hughes, honored the Renaissance Casino College Formal in a 1925 poem.

College Formal: Renaissance Casino

Golden Girl

in a golden gown

in a melody night

in Harlen town

lad tall and brown

tall and wise

college boy smart

eyes in eyes

the music wraps

them both around

in mellow magic

of dancing sound

till they're the heart

of the whole big town

gold and brown

In 1923, the BALL in ballroom took a different spin, becoming a basketBALL court during home games for the former Spartan Braves, the first owned-and-operated, all-Black professional team. That year, basketball manager, Robert “Bob” Douglas made a deal with owner William Roach to rename the team from the Spartan Braves to the Rens, if the stately building would host the team. The Rens were a leading contender for the Black national championship title, but they had no home court. The Rennie was centrally located, had a spacious floor that could accommodate basketball games and even a balcony where fans could look down at the action on the court and cheer on their team. The team’s first players included Clarence “Fats” Jenkins, James “Pappy” Ricks, Frank “Strangler” Forbes, and Leon Monde. All four were highly acclaimed athletes who had also played professional baseball in the Negro Leagues. They would go on to be celebrated collectively as part of the 1932-33 team that was inducted into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame as a unit in 1963. In the 1924-25 season, the “Rens” won the first of many Colored Basketball World Championships. But from their homecourt in the Rennie, they not only dominated Black basketball, but all of the sport for the next quarter of a century. The Rens triumphed over championship-caliber white basketball teams such as the Original Celtics, the Philadelphia SPHAS, the Oshkosh All Stars, and the Indianapolis Kautskys. Although the all-Black Rens smoked their opponents, the white teams did not allow African American players on their teams. In 1939, the New York Rens won the inaugural World Championship of Professional Basketball, an invitation-only tournament featuring America’s twelve best pro hoops teams. The Rens defeated the Oshkosh All Stars, the champion of the white-only National Basketball League, becoming the first Black team to win the all-white league. "That was a special aspect of what the Renaissance Casino and Ballroom was all about. They had basketball, sports and music all at the same time," Kareem Abdul-Jabbar stated.

The multi-use Rennie hosted other sports events. Bicycle races and other competitions garnered community support. When Joe Louis defeated the German boxer, Max Schmeling, in a 1938 rematch, the nation celebrated—and one of the biggest parties was at the Rennie. The police commissioner closed off thirty blocks so that over 100,000 revelers could party in the street.

The Renaissance complex truly was the center of the community and racial pride. Not only was it the place for parties, community events, fundraisers, assemblies, political rallies, dance marathons, wedding receptions, college formals, and debutante, cotillion, and masquerade balls, it was utilized by prominent organizations like the NAACP, Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, Business and Professional Men’s Forum, and many others. African American achievements were lavishly praised and advertised.

“The destruction of the Renaissance Ballroom Casino Complex is a cultural and historical catastrophe.”—Michael Henry Adams

But what happened to this Harlem palatial, yet welcoming, bastion of Black culture? For decades it thrived and cultivated arts, community, ideas, sports, and many genres of entertainment. Its energy began to dissipate and by 1979, it had closed and looked abandoned. The Rennie began to shed its elegant exterior and became so dilapidated that film director, Spike Lee, used it as a set for a crack house in one of his films. Then, in 1989, the neighboring Abyssinian Development Corporation (ADC), a nonprofit established by Abyssinian Baptist Church purchased the Rennie. They stated that their intention was to preserve and restore the building to its original magnificence. There were even discussions about getting the New York City government to declare it a landmark, thereby protecting it. But, in 2014, ADC sold it to a real estate development group, claiming that the old structure needed to be demolished and replaced by an eight-story residential tower with affordable housing for Harlemites that would be also named the Rennie.

The plan was not a popular one with Harlem activists, historians, and scholars. Save Harlem Now! organized a protest from October 2018-April 2019, and on the day of the demolishment, the organization’s primary activist, Michael Henry Adams, was arrested for trying to stop the demolition. Save Harlem Now! had explored every possible resolution to save the grand building and had some interest from a few city agencies, but, in the end, the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC), refused to save the Rennie.

Today, luxury condos suffocate the grounds that once held up the Harlem Renaissance Ballroom and Casino, the center of one of the most auspicious eras in Harlem’s history. Called the Rennie, the new apartment building is made of glass and steel. It’s dull gray and brown does not reflect a kinship with African design. In the condo descriptions, the use of the antiquated racist and misogynist term, “master bedroom,” is utilized, making one wonder if the builders knew anything about the heritage of the land. The least expensive unit is a studio apartment, which sells for more than half a million dollars. Community residents have a different definition of affordable housing, but once again, people with money win.

In placing a marker at this site, While We Are Still Here honors the agency and perseverance of the Rennie’s founding visionaries who endeavored to build an institution for our people. Their memory must be honored and respected.

Copyright © 2025 While We re Still Here - All Rights Reserved.

Powered by EM Designs Group

Cookie Policy

This website uses cookies. By continuing to use this site, you accept our use of cookies.