MARKER BIOGRAPHIES

lewis michaux

2107 Adam Clayton Powell Ave.

African National Memorial Bookstore 2101 7th Avenue and Lewis Michaux

“Knowledge is power; you need it every hour. Read a book.”

“Words. That’s why people need our bookstore.”

This house is packed with all the facts about all the Blacks all over the world.”

— Lewis Michaux

The African National Memorial Bookstore boasted thousands of volumes of fiction, non-fiction, maps, posters, brochures, pictures, and reference books. The “house” was packed from floor to rafters and overflowed onto bins on the sidewalk, but the crowded shop wasn’t bursting with just any books. Shelves were filled from top to bottom with literature written by and for African Americans, Africans, and other people of color. Lovingly referred to by founder/owner, Lewis Michaux, as the "House of Common Sense and the Home of Proper Propaganda," the most prominent Black bookstore in the country had a rough beginning.

The self-taught scholar and civil rights activist, Mr. Michaux, arrived in Harlem with purpose, moxie, and determination. He was sent to New York by his brother, Pastor Solomon Lightfoot Michaux, to recruit people for the National Memorial to the Progress of the Colored Race in America, an 1100-acre farm on the James River in Virginia, an ambitious initiative of Pastor Lightfoot’s church. Mr. Michaux did his best to sign up people from the organization’s office near 125th Street, but city folk didn’t seem to be interested in farming and, also, those who had migrated North had no desire to return to the South. Recruitment efforts failed. However, Lewis decided to use the storefront office for his dream of creating a book store that celebrated Black books. There were a few obstacles: he had no money; no books; no retail standing in the community; the rent was paid for just a few months; and publishers were not exactly printing a copious amount of works by Black authors in the 1930s. Michaux was accustomed to following his heart, no matter the consequences, so he was undaunted by the seemingly overwhelming barriers in his path.

Michaux grew up in a large family in Newport News, Virginia, and was the most rebellious of the eleven Michaux siblings. His father ran a successful fish and produce store and although he wanted his children to succeed him in the business, none were interested. Little Lewis, along with his brothers and sisters, often worked in the store, but the best time he had with his father was when they were discussing Black culture, history, and leaders like Marcus Garvey. From a young age, Michaux had a strong sense of pride and keen awareness of racial inequality; he refused to accept the status quo. His parents recognized his sharp wit and intelligence, but they worried that he may be too clever for the times. As a teenager, he briefly worked for a white farmer picking blueberries—hard work for very little pay and he came to the conclusion that the farmer was prosperous because he was exploiting Black children to do the heavy lifting while he relaxed in the shade. Lewis quit his job because he felt the dominant culture acquired wealth by stealing from poor and/or people of color. Sometimes in trouble with the law for earning money by illegal means, he preferred the consequences of committing a crime over being exploited. He relocated to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and operated a profitable, but unlawful, gambling parlor, which led to a severe beating from the police. The battering severely damaged his face and for the rest of his life, he wore a glass eye.

Pastor Lightfoot, the first African American to broadcast a radio religious program, appealed to the court to release Lewis into his custody so the younger brother could work for the church and mend his ways. Lightfoot was on good terms with several US presidents and other prominent politicians and created change in his own way. Although the pastor’s prominence helped Michaux stay out of jail, he did not see serving the Lord as a career. Michaux said, "The only lord I know, is the landlord." Lightfoot and his wife, Mary, frustrated by the younger brother’s disinterest in religious life sent him to Harlem to proselytize and round up supporters. Michaux, a loyal Garveyite, was finally in Harlem, the center of Black America, and saw the opportunity to create a hub for revolutionary thought and study, and to educate people about Black nationalism. To honor his brother’s mission, he named his shop, the African National Memorial Bookstore.

Free of the law and his brother’s church, Michaux opened up the bookstore with about five donated publications by Booker T. Washington, and others written about Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, Mary McLeod Bethune, and George Washington Carver. He was heavily influenced by Frederick Douglass’s belief that literacy was the door to knowledge and therefore freedom. Like the abolitionist Douglass, Michaux viewed books as a way to share ideas as well as to learn.

The struggle for the bookstore continued. He applied for a business loan from a local bank. The loan officer encouraged him to ask for funding for a fried chicken establishment, which would certainly be more successful because “Negroes” would eat, but would never read a book. Undaunted by such ignorance, he loaded his books into a pushcart and peddled them throughout Harlem, shouting out rhymes like: “You are not necessarily a fool because you didn’t go to school!” “Don’t get took, read a book!” “Negro is a thing, use it, abuse it, accuse it, refuse it.” His performance quality sparked a following and people began to patronize the bookstore. Lewis’s fortitude to create a repository for Black literature was a calling rather than a business plan. To keep his dream alive, he washed windows, performed a variety of odd jobs, slept in the store since he didn’t have money for an apartment and lived a frugal life, often choosing to buy books rather than food.

While in Philadelphia, he met Richard Wright, founder of the first African American Trust Company, as well as the first African American Bank in the North. Wright, who had founded what is now Savannah State University, had studied at Wharton, Harvard, Columbia, University of Chicago, Oxford University, and the University of Pennsylvania and had also achieved the rank of major in the army. As the army paymaster, he held the highest position of any African American in the armed forces. Michaux traveled to Philadelphia to ask the distinguished and celebrated Major Wright for a loan and, although Harlem was out of the bank’s jurisdiction, the banker recognized the brilliance and backbone of Lewis and in 1939 lent him $500. In today’s market, it would amount to almost $12,000. Lewis Michaux finally had the financial backing he needed.

In just a few short years, the pushcart bookseller became known as “the Professor” because he knew just almost everything about Black culture and history. His African National Memorial Bookstore had transformed into a hub of learning, exchange of ideas, and liberatory ideology. He featured a Black Hall of Fame section and honored Black voices from around the world. Michaux knew every nook and cranny of his crowded establishment and often gave away books to those who could not afford them. “My primary mission is to put books in the hands of Black People,” he said and that’s exactly what he did. Often, he locked the door, leaving studious patrons inside to spend the night garnering knowledge and absorbing the written word. His advice to young people, “You go on to school. There are things you can learn from your teachers, but don’t stop thinking for yourself. And don’t you stop asking questions.”

Many authors, leaders, and philosophers frequented the stacks over the years. W.E.B. Du Bois, Malcom X, James Baldwin, Muhammad Ali, Zora Neale Hurston, Nikki Giovanni, Langston Hughes, Louis Armstrong, Claude McKay, Eldridge Cleaver, and John Henrik Clarke are just a few of the personalities who came for the great books and spirited conversation with Mr. Michaux. He hosted book launches and readings. The store’s façade was decorated with an array of slogans, facts, political information, and truth, but the establishment was not relegated to the building. Michaux set up booths at a variety of events and even built a platform on the sidewalk in front of the store so that Black leaders and thinkers could give speeches to the community. From the platform, he called for Black people to learn their history by reading books. He said, “If you don’t know and you ain’t got no dough, then you can’t go, and that’s for sho.”

In 1968, the store was forced to move to make way for a New York State office building. Pastor Lightfoot’s ally, Governor Nelson Rockefeller, intervened on the cherished store’s behalf ensuring that it could relocate to 101 West 125th St. Although the patrons followed Michaux, he was not happy with the new place. In 1973, he was diagnosed with throat cancer; his wife continued to run the business while Lewis healed. In 1974, the state planned to erect another office building at the new location. Lewis closed the store. He passed away in 1976. For several years after the Professor’s death, Harlem’s Studio Museum held the annual Lewis H. Michaux Book Fair in his honor. At the beginning, the African National Memorial Bookstore had less than ten books, but at its closing it boasted a collection of more than 200,000 texts, and had earned the reputation of being a major landmark for the Civil Rights Movement. And the witty, poetic, scholarly Michaux had stimulated an entire generation of students, intellectuals, writers, and artists.

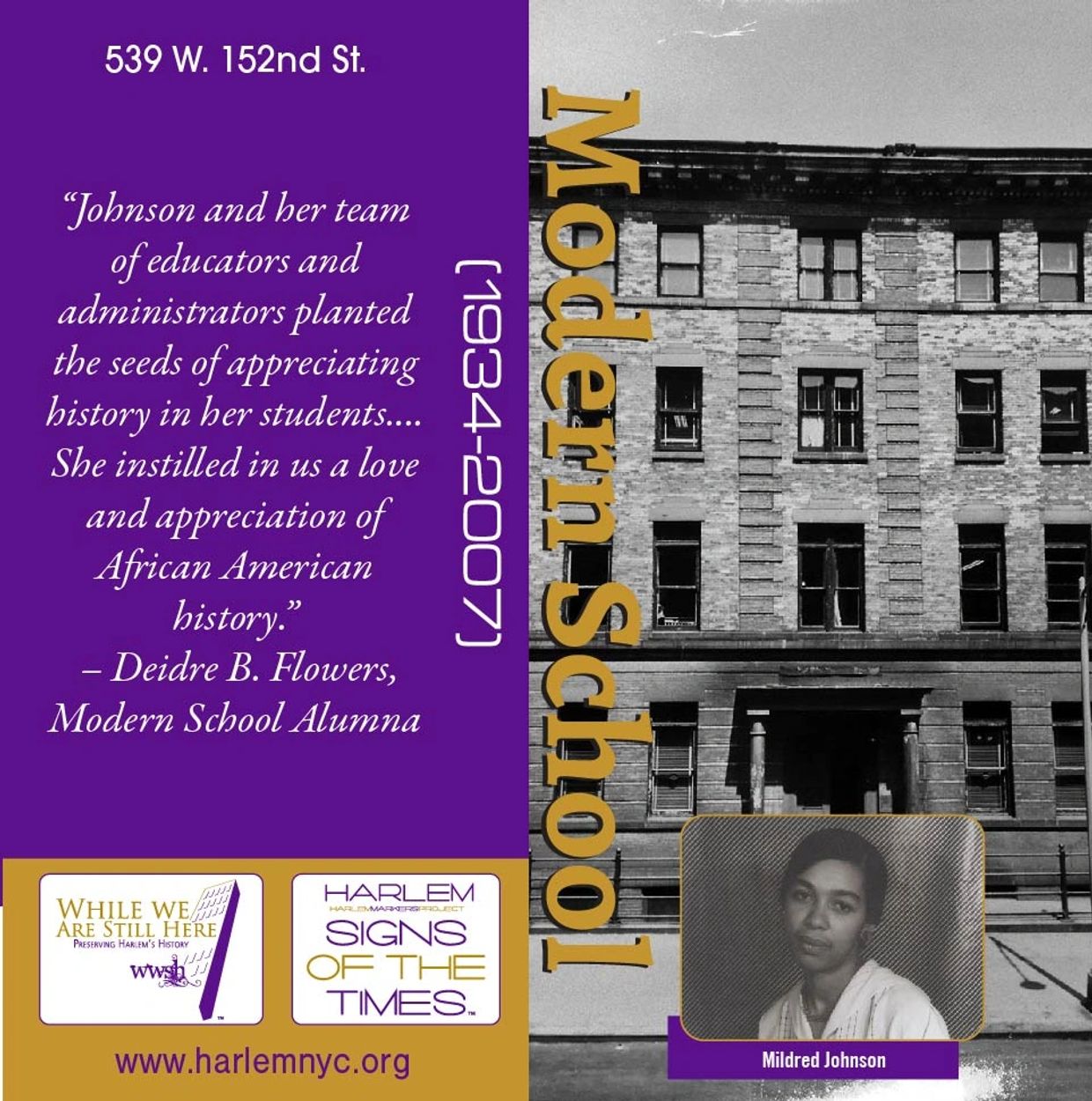

the modern school

539 W. 152nd St.

More information coming soon

queen mother audley Moore

1901 Amsterdam Ave.

“I had two guns—one in my bosom and one in my pocketbook . . . Everybody was told, and everybody knew they had to come armed. We wanted that freedom.” — Queen Mother Moore

Audley “Queen Mother” Moore, a self-taught scholar, was a follower of Marcus Garvey and anticipated his visit to New Orleans. However, the police had threatened serious consequences to anyone who attended the Garvey rally. Black organizers responded by urging everyone to arm themselves and show up to hear the powerful founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). Twenty-two-year-old Moore, not only attended, but was prepared for an armed confrontation with law enforcement, packing firearms and exuding confidence, bravery, and determination. She stood amidst a throng of Black supporters, all with their guns drawn and chanted with the crowd, “Speak, Garvey, speak!” Moore recounted, “The police filed out of there like little puppy dogs wagging their tails. They knew they would have been slaughtered in that hall that night. Because nobody was afraid to die. You’ve got to be prepared to lose your life in order to gain your life.” The event solidified Moore’s fortitude to devote her life to one of activism, Black nationalism, and freedom. Until her death, she remained a protector, leader, and galvanizer.

Tulane University (once named University of Louisiana's School of Medicine), in nineteenth-century New Orleans, Louisiana, was a bastion for white academics to legitimize racism by inventing pseudo- scientific codifications of race and false depictions of human beings. The city subjected its Black, Indigenous, and Italian citizens to Jim Crow laws and some of the harshest treatment in the South. Marcus Garvey may have set his sights on carrying his message of unity and strength to the very place that had sent out racist “scientists” to spread their vile messages of polygenesis, distorted rationalizations for slavery, and other unscrupulous, fake theories based on shoddy research, which resulted in many atrocities committed against Black Americans under the guise of real science. Many of these ersatz “scientific” concepts still persist and were rampant in Audley Moore’s New Orleans of the 1920s. Tulane scientists and others helped turn white supremacy into a “rational” science.

Moore was a transplant to New Orleans from New Iberia, Louisiana, where she grew up with more advantages than other African American children of the times. She and her two sisters attended a fairly good Catholic school and had private music lessons. However, first her mother died and when she was a teen, her father passed away leaving her to care for her younger sisters. So Moore quit school and lied about her age so she could be admitted to a cosmetology program to provide for the family by working as a hairdresser. New Orleans was a tough city for any person of color, but particularly for a teenage girl with adult responsibilities. Moore read the Black scholars and activists of the day, becoming a literate proponent of revolution. She said, “Garvey brought me a new consciousness in relation to Africa and the connection with the Caribbean. I didn’t know my connections with the West Indies and neither did I know my connections with Africa.”

Moore married a Jamaican sailor and they set their sights on moving to Africa. Their journey took them far from New Orleans, but they never got to relocate to Africa. First, they moved to California, then Illinois, and eventually, they migrated to Harlem during the Great Migration in 1922. Moore joined the UNIA and soon moved into a leadership position within the organization. She recounted that one of her proudest moments was of becoming a shareholder in the Black Star Line. Moore organized UNIA conventions in New York and was quoted as saying, “I have done everything I could to promote the cause of African freedom and to keep alive the teaching of Garvey and the work of the UNIA.”

The UNIA was the largest African organization in the world with 1,000 divisions and six million members in forty countries. But, as the movement gained members and influence, it was constantly under attack by the US government. Garvey’s leadership was cut short in 1923 when he was indicted and convicted of fraud and in 1927. President Calvin Coolidge pardoned, but deported him. Although the UNIA was destabilized, many members kept its values alive. Queen Mother said, “he [Marcus Garvey] brought something very beautiful to us — Africa for the Africans. That was our inheritance. Africa for the Africans at home and abroad. That we were somebody. […] That we had a right to be restored to our proper selves.”

Moore turned to the Communist Party (CP), becoming nationally respected for her organizing abilities. During the 1930s and 1940s, the CP promoted the “Black Belt Thesis,” advocating for the right of African Americans to secede and form a separate nation within the United States. This idea was aligned with Moore’s Garveyism beliefs. Moore returned to Louisiana to organize in the late 1950s, where she led rent strikes, school desegregation challenges, voter registration drives, reparations agendas, and women’s and civil rights organizing. She founded the Universal Association of Ethiopian Women (UAEW) and, from 1957 until 1963, this small but impactful association fought for welfare rights, helped exonerate wrongfully accused and convicted Black men, and taught Black women how to rally for their rights. Moore said, “Our purpose in life is to leave a legacy for our children and our children’s children. For this reason, we must correct history that at present denies our humanity and self-respect.”

Moore encountered racism within the Communist Party, plus the “Red Scare” undercut her organizing networks. Undaunted, she continued developing her own brand of radical grassroots organizations in the next two decades and founded several more organizations. She is often credited with jumpstarting the struggle for reparations for descendants of enslaved Africans. In 1957, during the peak of the Cold War, Moore addressed the United Nations, presenting a petition demanding land and billions in reparations for people of African descent as well as assistance for those who wanted to immigrate to Africa. She created the Committee for Reparations for Descendants of U.S. Slaves, and The Republic of New Africa in 1963, calling for self-determination, land, and reparations for African Americans. An advocate for the rights of those incarcerated, especially the wrongfully convicted, Moore challenged racism in the penal system and gained a following throughout the country’s prisons.

Queen Mother Moore’s determination and selfless efforts helped create and guide a new generation of nationalist organizers. Men such as Malcolm X sought her counsel and she mentored many, helping them develop revolutionary ideology and practice. For the rest of the twentieth century, she not only nurtured Black nationalists and advocated for reparations, organizing through Black Power-era organizations such as the Republic of New Africa and the BlackPanther Party, but she was active locally. Highly regarded nationally and internationally, she humbly joined local parents and teachers in the 1966 sit-in at a Board of Education meeting in Brooklyn, demanding funding equity in African American community schools. Moore also served as the bishop of the Apostolic Orthodox Church of Judea and co-founded the Commission to Eliminate Racism, Council of Churches of

Greater New York.

The Queen Mother did make it to Africa while traveling the world in the 1980s and 1990s. She often joined notable activists like Nelson Mandela galvanizing support for Black communities both here and abroad, and celebrated when countries became independent from their European colonizers. In 1972, Moore traveled to Ghana to attend the funeral of former Ghanaian president, Kwame Nkrumah. An Ashanti delegation formally recognized her noble contributions by gifting her the honored title of Queen Mother of the Black Freedom Movement. Over a decade later, Audley Queen Mother Moore and forty other courageous, Black American women were honored in the 1989 Brian Lanker photography exhibition, “I Dream a World,” at the Washington, DC Corcoran Gallery of Art. The Queen Mother’s final public appearance was at the Million Man March in 1995.

Copyright © 2025 While We re Still Here - All Rights Reserved.

Powered by EM Designs Group

Cookie Policy

This website uses cookies. By continuing to use this site, you accept our use of cookies.